Buckley and Buckley Offer Insights for Philanthropy from Founding Funding Plan for National Review

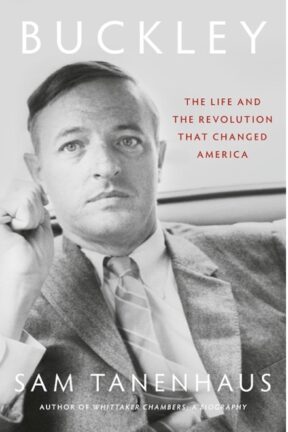

As young William F. Buckley, Jr., and others were working to launch National Review in 1955, it “needed backers and donors,” of course—as Sam Tanenhaus writes in his new biography Buckley: The Life and the Revolution That Changed America. This was a challenge. “There must be a body of knowledge to fund-raising; but they don’t teach it at Yale,” Tanenhaus reports 29-year-old Buckley as saying.

Buckley and former Time editor Willi Schlamm, who helped persuade him to start the magazine, “had a novel idea: their magazine would actually make money,” Tanenhaus writes. “They both knew how far-fetched this was. Even in the best of times ‘little magazines’ were sinkholes.”

Far-fetched then, as now, for any opinion journal—perhaps especially for one professing belief in the free market, Buckley thought, according to Tanenhaus. For Buckley, it was an idea worth straining to pursue, though—if even only for intellectual consistency, in which he also believed and which mattered very much to him.

“No one could honestly object to a liberal magazine that subsisted on charity,” as Tanenhaus describes Buckley’s thinking.

It was fully in keeping with the “statism” of the New Deal programs The New Republic had supported. But Buckley had promised something different. “The only weekly of opinion that stands on the side of free enterprise” would itself live out the free-market creed. It would be something new: a serious political journal that sustained itself fiscally. Buckley even promised that it would turn a profit.

So, following the outline of a plan drafted by Bill Casey to attract investors, by Tanenhaus’ telling, “Schlamm drew up a plan to raise $490,000—eventually lowered to $450,000, far below the $1 million or even $2 million” that Henry Regnery

was telling people they would need—with debentures issued to a total of 120 investors. The debentures would be divided into slightly unequal portions of voting stock, the donors collectively in control of 49 percent of the shares, Buckley, in dual roles as published and editor, controlling 51 percent. Just as Willi had said from the beginning, it would be Bill’s magazine and his alone.

In other, perhaps-cynical words: the investors’ money would be great; any of their advice and guidance that need be heeded, not so much.

Perhaps less cynically, according to John B. Judis’ earlier, 1988 biography Wiliam F. Buckley, Jr.: Patron Saint of the Conservatives, Buckley’s controlling share of stock was “so that factional disputes would not be able to destroy the new magazine as easily as they had destroyed The Freeman”—the libertarian magazine launched in 1950 as a for-profit that after internal division and turmoil, was turned over to the nonprofit Foundation for Economic Education (FEE) by the middle of the decade. As a for-profit, another little-magazine “sinkhole,” though FEE was able to use it to help raise money. “The Freeman had splintered as a result of too many people owning stock,” Judis quotes Buckley as saying. “There are a number of difficulties that you don’t have if you own all the stock.”

As for Buckley’s firm control of NR, Judis quotes him as saying,

I remember Willi announced it to me as definite that I was going to start it. Willi was capable of flattery, but the point was not flattery. It was much easier for a 29-year-old to be editor in chief of a magazine with these giants then for a 39-year-old or a 49-year-old, because people are willing to do favors and be condescending toward someone who was 25 years younger than they. They would not consent to be in a situation that was organically competitive.

Judis notes that Schlamm, one of “these giants,” didn’t think the arrangement “was reducing his own role in the project” and that he felt he could exercise much influence over Buckley and his leadership of it. In formal legal structures and informal human relationships, after all: there’s control, and then there’s control, as well as influence, and then influence.

In the plan for presentation to potential NR investors, Tanenhaus reports, Schlamm “roughed out ‘an informed guess’ at a budget” for the new publication and included, “most dreamily, a projected ‘gross profit per year’ of $136,000.” Judis writes that Schlamm’s work of salesmanship “exhibited what Buckley later called Schlamm’s capacity for ‘hype.’

“I am a rotten salesman,” Tanenhaus also quotes Buckley as lamenting—“but he nevertheless resigned himself to spending the next months ‘importuning people and making a terrible nuisance of myself,’” according to Tanenhaus, quoting Buckley. “Buckley might be brilliant, articulate, impassioned, energetic, confident, and good company,” Tanenhaus writes. “But he was also extremely young, and his start-up funds so far had come entirely from his father,” who’d contributed an initial $100,000, “which led some to wonder why the wealthy Buckley Sr. didn’t pay for the whole thing.”

According to a Tanenhaus endnote, “David Lawrence, the conservative columnist who also the founding editor of U.S. News & World Report, advised WFB to set up his magazine as a nonprofit and seek donors willing to absorb losses.” Buckley and Schlamm had hoped to recruit either Lawrence or Newsweek’s Ralph de Toledano to be NR’s managing editor, by Judis’ telling—neither of whom wanted “to leave secure and remunerative positions for a magazine that appeared to them very chancy.”

Buckley declined to accept Lawrence’s advice that NR go nonprofit, opting instead to pursue the for-profit plan—the informed but dreamy one, optimistically rounding up on expected numericized outcomes, that would carefully and purposely allow Buckley to retain control of the enterprise, however far-fetched he might’ve felt its actual for-profitness. The first issue of NR was published on November 19, 1955.

From Founding for- to Sustaining Non-

Three and a half decades later, though, came the National Review Institute (NRI)—a nonprofit public charity that was a financially supportive, but organizationally separate partner of National Review. “The Institute started in the early 1990s, when a couple people—leadership of the magazine and friends of the publication—realize[d] that it needed a nonprofit element and needed a nonprofit arm,” according to NR editor-in-chief in a 2020 NRI video. After Ronald Reagan’s departure from the presidency and American public life, and funding challenges persisted through the decades, “National Review found itself in a situation in which it was a bit uncertain about its future as a magazine,” onetime NR editor and longtime editor-at-large John O’Sullivan says in the video.

“We were kind of struggling and trying to figure out a way to make sure that National Review and the legacy of William F. Buckley, Jr., would live on,” says Lisa Nelson, NRI’s founding executive director, who’s now president of the American Legislative Exchange Council. “We needed an angel, and we needed an angel who was actually active, and we found that angel in Palm Beach,” O’Sullivan adds.

That angel—NRI founding chairman Gay Hart Gaines—then remembers “inviting some of the National Review favorites down to Palm Beach with Stanley and me, and that was in early 1990. We had Wick Allison and his wife; Dusty Rhodes” of Goldman Sachs “and his wife Gleaves; John O’Sullivan the editor; Lisa Nelson; and Mike Joyce, and his wife Mary Jo, from the Bradley Foundation,” the conservative nonprofit private foundation on the board of directors of which Rhodes also later served, including as chairman.

“I said, You know what, we’re all going to go into the sunroom and we’re going to think about something bigger that we can do,” Gaines continues.

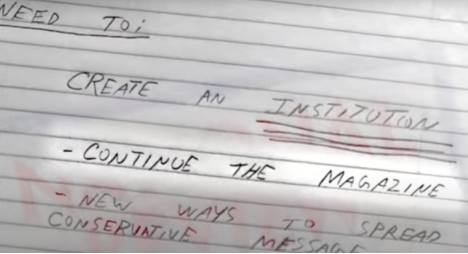

The big thing was, How can we get an institution that will mean the magazine can continue more or less indefinitely, but that also develops other ways of broadcasting the conservative message to millions of Americans who otherwise wouldn’t hear it? And the answer was the National Review Institute. It was through that weekend that National Review Institute was conceived of and really created.

From portion of 2020 NRI video about its creation

From portion of 2020 NRI video about its creation

From 2010 to 2015, National Review received a total of $266,060 in support from private- foundation grantmaking, according to a 2018 report from the Harvard Kennedy School’s Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy. This amount makes NRlast on the report’s list of the top 25 foundation-funded magazines during the period, equals 0.3% of all $79,618,606 in foundation support for those 25 magazines, and is considerably less than that for the only four other magazines categorized as conservative on the list—The New Criterion (No. 5, at $4,198,282, five percent of the total to the top 25), Commentary (No. 11, at $1,574,550, two percent of the total), The American Spectator (No. 15, at $1,152,740, one percent), and Reason (No. 19, at $688,000, another one percent, given rounding).

In 2015, as NRI recounts elsewhere, the for-profit entity controlling both National Review and its website—corporately National Review, Inc.—became a wholly owned subsidiary of the nonprofit NRI public charity. NRI’s total revenue, including from individual and foundation donations, in 2015 was $329 million, according to its publicly available tax filings; in 2024, the most-recent year for which figures are available, its total revenue was $8.95 million. It seems fair to infer that most individual contributions were from those that also subscribed to NR.

For NR, it also seems as if the full-on for-profitness that Buckley and Schlamm felt in 1955 might be too far a fetch ultimately became just that, in fact, by 2015.

Motives and Money, “Purchase” and Power

Perhaps only “ultimately,” however—or, at least, only after the six decades that has passed since Lawrence’s original advice to opt for nonprofit status. As a thought experiment from which to perhaps gain insight, it’s worth hypothetically contemplating what might have happened had Buckley pursued Lawrence’s suggestion to found National Review as a nonprofit in ’55, including what would have been the ramifications for Buckley, the magazine, and “the revolution that changed America,” in the words of Tanenhaus’ subtitle.

First and foremost, there would have had to be grant proposals submitted to philanthropies, with a plan. It is plausible to theorize that such a submitted plan would have been as informed but dreamy, as optimistically “rounding up” on expected outcomes, as Casey’s and Schlamm’s—but not retaining the kind of control of the project by the founder that their for-profit plan did. That would have been difficult. There would thus have been risk to the mission, the vision, and what became the revolution. Casey’s and Schlamm’s private-investor route had risk, too, of course, but much less—at least to that which might’ve mattered most, in this case reliance on and thus control by Buckley.

The difficulty for Buckley to retain control of NR as a nonprofit grant recipient would have been because of what mostly progressive critics of philanthropic support for their activities historically have termed “movement capture.” Acknowledging potential oversimplification: movement capture is the process by which private funders—often well-intentioned foundations or wealthy donors—use their financial leverage to influence, redirect, or moderate the agendas of social movements and activist organizations. The younger a movement or organization, of course, the more likely any attempted capture of it is to succeed. In other words: new groups are more “purchaseable.” And, by the way, probably cheaper.

While it might be tempting to think that a group’s private, stock-holding financial investors—supposedly motivated by the specter of a profit—would also be in a position to “capture” and influence, that’s a little bit of a non sequitur. They’d already own it; it’d be captured from the get-go. What I’ll call the Casey-Schlamm plan “gave away” 49% to keep the controlling 51%.

Philanthropic funders of nonprofit publications “actually have far less influence than the owners of for-profit” ones, former ProPublica president and Wall Street Journal executive Richard J. Tofel told me last year. Grantmakers to nonprofits are

more in the position of advertisers. … [F]or instance, at the Journal these days, I strongly suspect that Rupert Murdoch does occasionally know what’s going to be published before it’s published. I don’t think, though, that the advertisers at the Journal ever do. The donors at a place like ProPublica have been put in the category, in terms of their ability to influence things, in the category of advertisers rather than owners.

In fact, “A lot of the money for nonprofit journalism comes from readers” and the power they can exercise, Tofel notes. “You are, I think, effectively dependent on your readers in ways … that people have not yet fully come to grips with.” Realistically, he says, the more-concerning question is “how much editors may be willing to discomfort their readers than how much they are willing to discomfort their donors or their advertisers.”

Which gives rights to another thought experiment that might yield insight: if NR were founded now, would it be a Substack newsletter and, if so, would it be pressured by the risk of “audience capture” to which both the Tofel-referenced nonprofit ‘little magazines’ and subscription-based Substack newsletters are sometimes subject?

Philanthropy Needs Deference Like the Casey-Schlamm Plan Purposely Structured

My two Giving Review co-editors and I worked at the Bradley Foundation when its chairman was Rhodes and its president was Joyce, who were both in the Gaines’ Palm Beach sunroom in the early 1990s when the nonprofit NRI was hatched to help “save” Buckley’s National Review. We certainly do not “speak for” Joyce, but we do think we learned a lot from him about how to pursue philanthropy in general and conservative philanthropy in particular.

I think Joyce would have understood and appreciated Buckley’s, Casey’s, and Schlamm’s desire—their structured plan’s purpose—to let Buckley run his own opinion journal in the mid-’50s. It was his project; it was dependent on his formidable talents, including his personality; they were his factions to manage; all of it his at which to fail. Deference to him was not only warranted, but deserved—in fact, more than 51% deference, for that matter. Just as, decades later, Bradley’s attitude would be: let the parents choose whether to send their kids to a school, and let the principal run the school; let the symphony director pick his or her own conductor and select what to play; let the neighborhood residents lead the way in deciding how to fight crime or clean the park.

If it was on the uniquely structured, for-profit plan that Buckley and his advisors settled to best preserve his control and singularly prominent role, all to the good, the thinking would’ve been. That’s their call. Were they to think it necessary or preferable to pursue philanthropic support via the means of a nonprofit, however—which became the case in the early ’90s—Joyce, making his call, would have urged it to his board. He’d have done so, though, without introducing to Buckley the originally feared risk of losing control. It was a large part of the way he did grantmaking, and there need be more of this way now, among all worldviews.

Grantmakers’ money is great, Joyce always knew; any advice and guidance that need be heeded therefrom by the grantee, not so much, he also knew. And try to make sure the grantee knows that, too, we learned from him. After a while, reputation will ensure wide knowledge thereof.

In fact, one of the best ways for a would-be grantee to become an actual one would be to make totally clear, by word and deed, that he was pretty much going to do what he was going to do anyway—with or without the stinking grant, and the control or influence its giver might exert, or the advice or guidance or detailed reporting requirements or demanded measurable outcomes that might come with it. Buckley, it seems, would’ve probably have convinced Joyce of that, whether it was with understandable but nonetheless-discounted salesmanship or not, in the mid-‘50s. Buckley did do what he was going to do anyway, after all, in what seems like would have been any way. His work surely so convinced those at the early-’90s sunroom summit.

Buckley helps show why the Casey-Schlamm arrangement made sense under the circumstances. The later Gaines’-sunroom one did, too. Were more of philanthropy to have the same deference detailed in NR’s founding setup, were there more belief and trust humbly placed by philanthropy in others than in philanthropy itself, and than in philanthropists and their employed professionals themselves, then hugely beneficial ramifications—as in this case for Buckley, the magazine, and “the revolution that changed America”—will follow.

This article first appeared in the Giving Review on July 14, 2025.

Source: https://capitalresearch.org/article/buckley-and-buckley-offer-insights-for-philanthropy-from-founding-funding-plan-for-national-review/

Anyone can join.

Anyone can contribute.

Anyone can become informed about their world.

"United We Stand" Click Here To Create Your Personal Citizen Journalist Account Today, Be Sure To Invite Your Friends.

Before It’s News® is a community of individuals who report on what’s going on around them, from all around the world. Anyone can join. Anyone can contribute. Anyone can become informed about their world. "United We Stand" Click Here To Create Your Personal Citizen Journalist Account Today, Be Sure To Invite Your Friends.

LION'S MANE PRODUCT

Try Our Lion’s Mane WHOLE MIND Nootropic Blend 60 Capsules

Mushrooms are having a moment. One fabulous fungus in particular, lion’s mane, may help improve memory, depression and anxiety symptoms. They are also an excellent source of nutrients that show promise as a therapy for dementia, and other neurodegenerative diseases. If you’re living with anxiety or depression, you may be curious about all the therapy options out there — including the natural ones.Our Lion’s Mane WHOLE MIND Nootropic Blend has been formulated to utilize the potency of Lion’s mane but also include the benefits of four other Highly Beneficial Mushrooms. Synergistically, they work together to Build your health through improving cognitive function and immunity regardless of your age. Our Nootropic not only improves your Cognitive Function and Activates your Immune System, but it benefits growth of Essential Gut Flora, further enhancing your Vitality.

Our Formula includes: Lion’s Mane Mushrooms which Increase Brain Power through nerve growth, lessen anxiety, reduce depression, and improve concentration. Its an excellent adaptogen, promotes sleep and improves immunity. Shiitake Mushrooms which Fight cancer cells and infectious disease, boost the immune system, promotes brain function, and serves as a source of B vitamins. Maitake Mushrooms which regulate blood sugar levels of diabetics, reduce hypertension and boosts the immune system. Reishi Mushrooms which Fight inflammation, liver disease, fatigue, tumor growth and cancer. They Improve skin disorders and soothes digestive problems, stomach ulcers and leaky gut syndrome. Chaga Mushrooms which have anti-aging effects, boost immune function, improve stamina and athletic performance, even act as a natural aphrodisiac, fighting diabetes and improving liver function. Try Our Lion’s Mane WHOLE MIND Nootropic Blend 60 Capsules Today. Be 100% Satisfied or Receive a Full Money Back Guarantee. Order Yours Today by Following This Link.